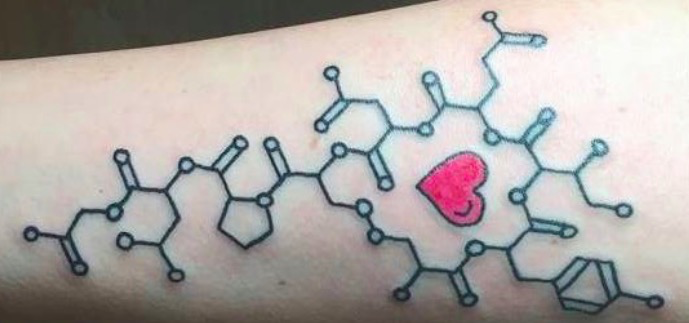

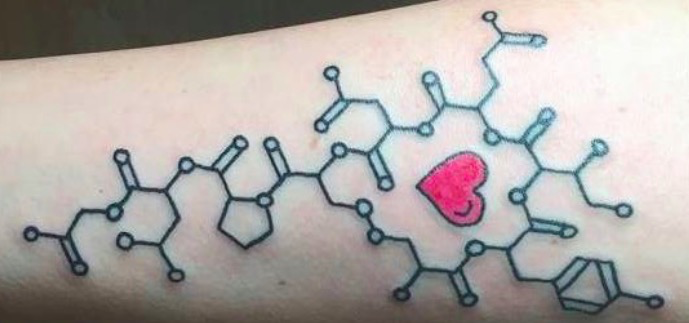

There are a few contenders, but oxytocin is probably our favorite hormone. Thought to promote a raft of cooperative behaviors and positive emotions, levels surge around birth for human mothers and during the infatuation phase of a blossoming courtship. In this sense, oxytocin is rather unique in that it bridges the long-term mutuality of loving a child with the spellbound craziness of falling in love with an admirer. No surprise that the so-called “cuddle chemical” has become synonymous with love itself. Embracing these passionate properties, artisans extol its virtues by crafting wearables (from bracelets to t-shirts) depicting its molecular structure.

The hardcore get it tattooed on their bodies.

Alas, oxytocin is not love. It is a peptide hormone and one of its purposes is to forge bonds with others in order to form a cohesive group. From an evolutionary perspective, the maxim “safety in numbers” makes sense here. In contemporary society, a cohesive group may be found on a battlefield in the form of a combat unit, on a street corner in the form of a gang or on a sports field in the form of a football team. It is also involved in any lifestyle identity we commit ourselves to; we are punk rockers, we are vegans and so forth.

In other words, oxytocin fosters a sense of “us”. But this has a second-order consequence: when there is an “us”, there is also a necessary “them”.

Contrary to popular opinion, what oxytocin actually does is exaggerate that space between “us” and “them”. This is the dark side of oxytocin. And “them” is its untold story. If a biography were written on oxytocin, “them” would be half the book. Yet “them” is virtually absent from our cosy oxytocin narrative.

It is not alone in this regard, other positively perceived phenomena also have a dark side; empathy can be destructive, bonding can be maladaptive, altruism can be pathological and, as those with straying spouses can attest, a kiss can encapsulate the ultimate form of betrayal. Indeed, kissing as symbolic of betrayal also has cultural resonance: for thirty silver pieces, this is how Judas identified Jesus to the Romans. Perhaps this is why Dante’s final circle of hell is treachery and why Jesus’s self-sacrifice became one of the cornerstones of Western civilization.

What we know about something can be skewed by the type of research we conduct on it. Or, put another way, where you look will determine what you see. Research designed to investigate the positive aspects of oxytocin, empathy, bonding or altruism will necessarily stress those qualities in the conduct of testing and in so doing, provide evidence for it. As empirical research seeps into our cultural consciousness, this influences what we come to believe.

For example, after the Holocaust the world was left aghast wondering how such a travesty could ever occur. Hannah Arendt captured the cultural temperature by coining the term “banality of evil” and psychology stepped up to figure it out. But in investigating obedience, conformity and the bystander effect, psychologists designed their research to emphasize those conditions which influenced our preference for compliancy, conformity and intervention reluctance. Sure, the likes of Milgram’s wickedly insightful shock experiments went someway towards explaining the Holocaust, but results were extrapolated outside those very unique conditions and this gave a distorted view of the human condition. Thankfully, subsequent research was more nuanced. You may be pleased to hear that we are not as obedient or conformist as initially thought and we can mobilize to action quite quickly indeed.

A critical factor in determining what we do is context; the situational conditions. Indeed, this is also why you may not be pleased to hear that we are not as obedient, conformist or reluctant as initially thought; it depends on what one is resisting or acquiescing to. Is a hammer “good” because it can be used as a tool to construct something objectively beneficial, or “bad” because it can be used as a weapon to destroy a kneecap? Sans context, obedience, conformity and intervention reluctance are better understood as amoral. Neutral. The same goes for oxytocin, empathy and bonding. Even your genes are impacted by your environment – hence the ever expanding field of epigenetics. The point is: how we choose to investigate something may skew our eventual perception of it. When that happens, we are left with lopsided understandings (and obscure oxytocin tattoos).

Nonetheless, it is not that difficult to conceive of positively perceived phenomena in a negative light; many of us know that particular someone who bonds dysfunctionally with a fruit machine, liquor or their work (the Japanese actually have a word for the latter; “karoshi” which translates literally to “overwork death”). Others may have had their empathy hijacked by a talented sales person who convinced them to buy a product they did not want (and still do not want – thank you very much). Manipulative seduction works much the same way and can leave long-lasting psychological gashes on its victims. But it is much more difficult to conceive of negatively perceived phenomena in a positive light. For some, incels are an utterly despicable lot; misogynistic, dichotomous, xenophobic, bitter, righteous and hellbent on violent reciprocity.

Or so the narrative goes.

For sure, some research will function to cement this view – which is somewhat troubling because humans have a tendency to conform to the labels they are given. But other research will move more cautiously and seek to understand this circumstance beyond its more nefarious and self-appointed representatives. The former will come thick and fast, the latter will trickle. This is unfortunate because a second-order consequence of framing incels as folk devils is likely to result in more victims of self-harm and public violence premised upon on a “hated ‘us’” and a “hating ‘them’”.

But “us-them” is not unique to incels and normies. It is hardwired in all humans and is primarily emotional, not rational. And it is through emotion that we find hope amidst the wreckage.

All of us have multiple “us” and “them” identities and we can flip these in an instant in the right context. That is to say, a “them” in one context can be an “us” in another; a uniquely human capability my now departed guinea pigs will never understand. For example, let us assume that I am an avid football player. Let us also assume that I am a white heterosexual Christian with decidedly negative views about non-whites, non-heterosexuals and non-Christians. One of my teammates happens to be black, homosexual and Jewish. On a crisp Sunday morning, our team assembles in matching attire to play our arch rivals. This is a big deal for both parties; bragging rights will persist until next season and anything less than a win will be enduringly shameful. Before the game begins, both teams engage in sportsmanship behavior and shake each others hands. But out of earshot of the referees, the other team whisper a volley of lurid remarks at Avraham. Indeed, these are remarks I may even agree with and remarks I may even have used on occasion after my favorite tipple loosened my inhibitions.

But not on this occasion.

Avraham, the black Jewish homosexual who embodies everything I disagree with, transitions to Avi my dependable teammate; his “transgressions” sidelined and his essence enveloped into an expanded sense of “us” which neither essentializes nor securitizes him. The other team’s attempt at splitting “us” apart by playing to my political sentiments and crushing Avraham’s sense of self actually resulted in a surge of in-group oxytocin; a jujitsu-like reaction where the power of “their” attack was constructively used to reinforce “our” cohesiveness.

Ideally, the context of this high-stakes football would be used to propel prolonged contact between myself and Avraham under the auspices of a superordinate goal (for example, coaching younger children where Avraham and I share the same purpose of modeling these budding players into as effective a football team as they can be). Over time and in so doing, my construction of Avraham would become more nuanced and individualized rather than framing him as just another black guy, gay guy or Jewish guy – pick your “them”.

This happened because I initially choose a bigger “us” over a smaller, fragmented and weaker one. I also chose to focus on those facets which I shared with Avraham rather than those which differentiated us. These are choices we all face and how we choose to act has direct implications for our sense of well-being, although we are not always as aware of our agency as we could be.

Before social science engaged the human condition with empirical tools, novelists did it with the written word. For example, in Crime and Punishment, Dostoyevsky plays out the consequences of different behaviors in response to suffering. One character violently retaliates against the supposed perpetrator of injustice. Another self-indulges in the numbing effect of alcohol in order subdue his anguish and attain temporary relief (read: denial). A third character, Sonya, responded by focusing her energy on the victims of injustice rather than lashing out against the personified source as Raskolnikov (the first character) did. Much like the conclusions of my doctoral dissertation, Sonya and Raskolnikov responded in morally opposed ways to the same antecedent conditions and motivations. In other words, the same diagnosis resulted in different prognoses. This, perhaps, is why Solzhenitsyn noted that “moving from good to evil is one quaver”. That which distinguished Sonya’s behavior from Raskolnikov’s was a subtle “quaver” indeed; she focussed on “us” victims and worked to lessen the collective suffering. He turned his gaze toward “them” perpetrators and worked to make them pay through retribution. Raskolnikov’s altruism went awry. Hers was constructive and filled with meaning and purpose (this is called the heroic imagination), his manufactured a succession of further suffering and brought him no personal relief (this is called the hostile imagination).

Incels exist on the extreme fringe of loneliness and their suffering is a legitimate grievance. But they are not the only ones bearing this load – loneliness is on the rise and this is what bridges “us” and “them”. How you choose to look at this will determine what you see. Do you choose to focus on your own suffering and hold society to task or do you foster an expanded sense of “us” and work to lessen the collective load, forging a sense of purpose in the process? In the clinical literature, Sonya’s response is termed as “altruism born of suffering” or “post-traumatic growth”. Social science and good literature suggest that this is the more beneficial one. Sacrificing your time and experience for others in a constructive manner brings a sense of fulfillment which reclusive, retributive and indulgent pleasures do not. The proposition here is to foster an expanded sense of “us” under the superordinate goal of sharing the experience of suffering with others in order to lighten everyone’s load. This will come across as rather blue-pilled of me, but all of “us” (incels and normies together) can cultivate a more resilient stance to insidious social circumstances if we choose to focus on those we share with each other rather than those which distinguish us. Oxytocin will do what its thing, but our limbic systems (the “emotional” parts of our brain) will set the boundaries between “us” and “them”.

A top tip as a postscript: if you’re going to get a pet, do not get guinea pigs.